Church of Saint Anthony of Padova

The construction of the current Chiesa di S. Antonio da Padova was started in 1635 on the side of the previous church on the site. It was built with the donations offered by the people of Mesagne and with the involvement of various members of the clergy; and above all, from the canon Francesco Venerio, chaplain and procurator of the previous church, which had already been cited in the pastoral visits during the 1500s and in the manuscript of the historian Cataldo Antonio Mannarino in 1596. In the following years until 1635 various acts of donation from the people of Mesagne were recorded. We have information about the church, not just from pastoral visits, but also from the Regio Tavolaro (royal engineer or architect) Pietro Vinaccia in 1731. Vinaccia describes a church with “a double-pitched roof…astregata in the ground, with an altar at the front”; a simple church therefore with just one altar. The historian Antonio Profilo at the end of the 1800s informs us of the archconfraternity that was most likely founded during the construction of the new church and that it “remained there until 1846, the year in which it transferred to the church of the Celestine fathers”. There is no record of the artisans that worked on the church, but it is most likely that the Profilos, who were very active in Mesagne during that period, were involved in its construction.

The church has one nave and externally presents as a single building delimited by pilasters, and with a broken pediment. After the earthquake of 1743, which probably caused some damage, the confraternity committed to other bodies of work, such as the sacristy built in 1749. At the start of 1763, the confraternity of Saint Anthony was given the title ‘royal’ by Ferdinando IV of Bourbon, and on that occasion, the confraternity commissioned a painting of the sovereign which still hangs in the sacristy.

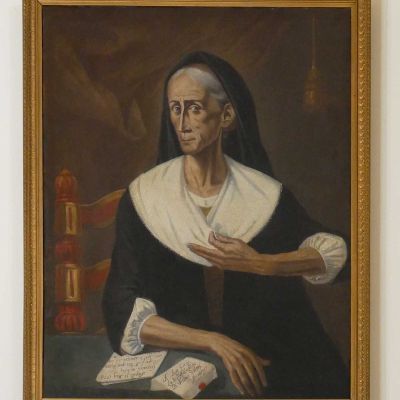

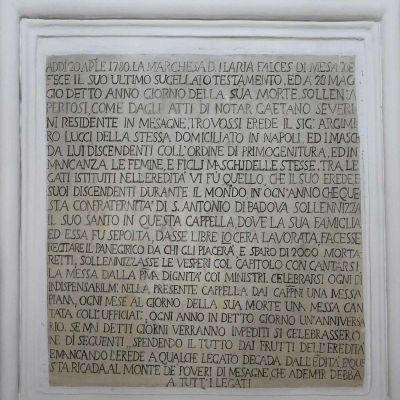

Another event of note relating to the Church of Saint Anthony of Padova is the institution of the monte di maritaggio (the practice of paying a tax for permission to marry) established by the noblewoman Ilaria Falces. This arrangement involved the poor of Mesagne and contributed to an increase in the numbers of worshippers at the church. Falces donated a considerable sum to the members of the confraternity in order to celebrate the saint, and also because of this, the church became important in terms of the 18th century events of the town. A document from the 30th October 1778 tells us that, at the end of the celebrations for the festival of the saint on the 22nd June 1777, a dowry was given to a zitella (spinster) that year in the presence of various believers and the fortunate person was a woman called Concetta di Vicienti. Inside the sacristy there is a canvas portrait indicated as Maria Falces; the woman depicted in advance age and in religious attire. It could be that ‘Maria’ Falces, of whom it is reported that she entered the convent of Santa Maria della Luce in 1715/16, is possibly ‘Ilaria’; i.e. that they are one and the same person. Inside, there are 18th century altars of the Sacro Cuore (Sacred Heart), Madonna del Carmine (Our Lady of Mount Carmel) and the chapels of Saint Joseph, and of the Crucified Christ.

Particularly lavish is the 18th century parietal painting of Saint Anthony of Padova found on the main altar. Also of note is the canvas from the second half of the 1600s depicting Saint Francis of Assisi worshipping the dead Christ supported by an angel on the counter facade. Two other canvases, one depicting Saint Anthony of Padova who is preaching to the fish, and another with the saint holding the feet of a youth, are both from the last quarter of the 1700s and from the Salento area. They are possibly from a different original location, as is the picture of Saint Irene from the same period. We can also speculate that the picture of the Padre Eterno (Eternal Father), dating from the end of the 1600s to the beginning of the 1700s, had a different original location due to the type of canvases used in the paintings. There are also additional canvases that depict the death of Saint Anthony who receives the Viaticum, and the Ecstasy of Saint Anthony at the point of death; both of which are from the last quarter of the 18th century.